When Corporations Practice Medicine

Guest Essay for THE FINE PRINT by Linda Peeno M.D. | December 17, 2024

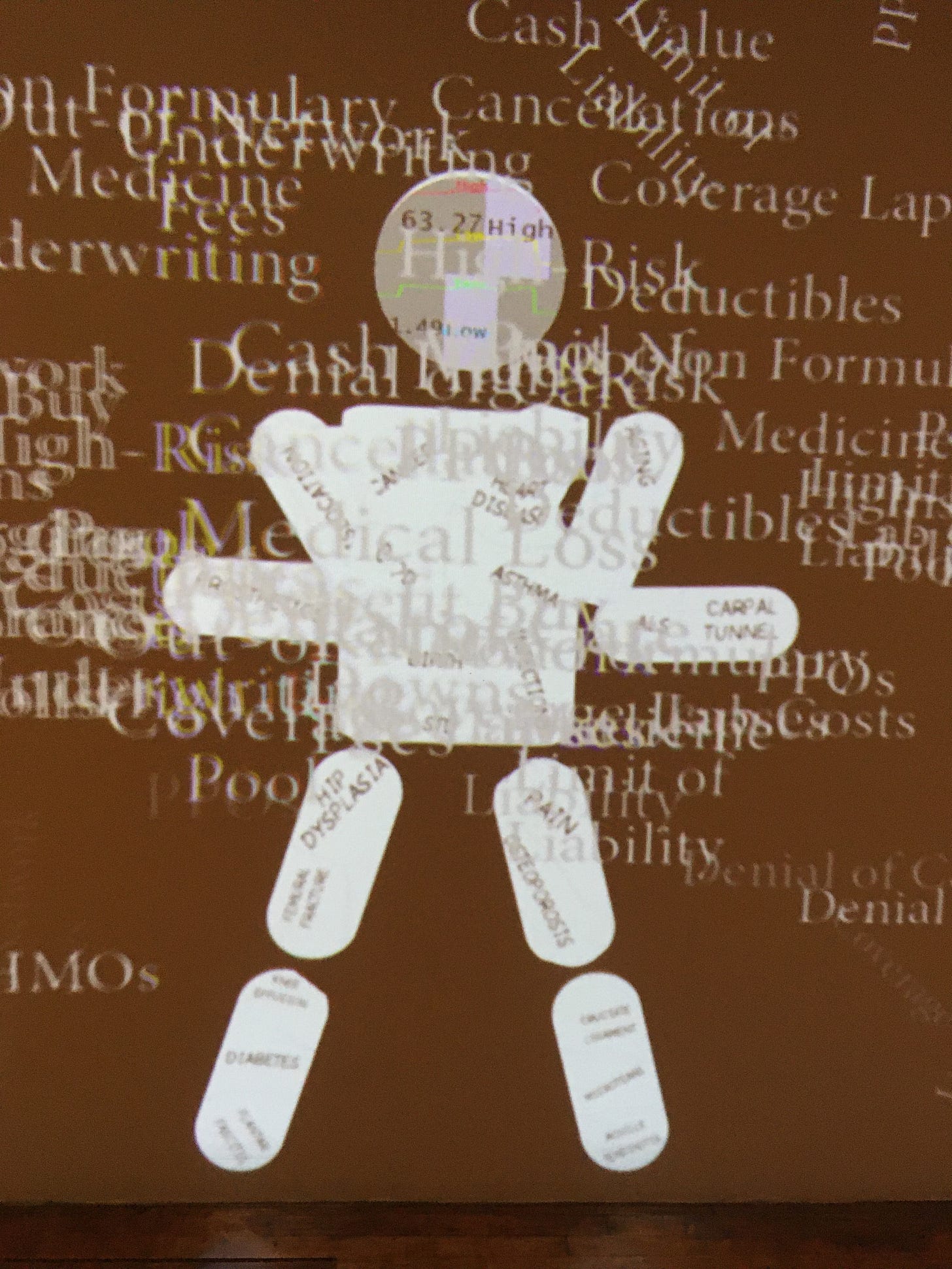

(“The Architects of Denial.” Multimedia art installation by Liviu Pasare for “SOME PEOPLE.” The Commercial Health Insurance industry invented a non-medical Denial of Care Harm-for-Profit vocabulary to intentionally drown patients in onerous administrative chaos. Chicago, 2019.)

“Too many things have happened

that weren’t supposed to happen,

and what was supposed to come about

has not.”

— “The Century’s Decline,” Wisława Szymborska[1]

D. died two deaths. The first, when they took his human being; the second when they destroyed his human meaning.

He was any one of us. He didn’t cause his fate, or deserve it. His life—hard worked and loving—was interrupted by an unexpected diagnosis of a rare, aggressive cancer. Fortunately, his condition arose at a time when modern medicine offered medical and technological advances that could have given him a reasonable chance of continued life and, unlike many Americans, he had insurance to provide him with that opportunity. Amazingly, his insurance company had recently developed a policy that covered the specialized treatment he needed. He could have been a 21st century success story.

Unfortunately, his insurance company and its employees, through their inexcusable, unconscionable, and negligent actions, took away his chance for survival.

There is no other way to describe this: he experienced an act of violence.

For what?

In an extensive analysis of “Corporate Crime, Corporate Violence,” two authors, Michael J. Lynch and Nancy K. Frank, write that “corporate offenders commit their crimes for one reason, and one reason alone: profit (italics mine).”[2] D. didn’t die in service of more efficient, higher quality of care—the mantra the industry has used for over four decades to justify their controls of the medical care of patients. It takes teams of well-paid company employees—including doctors and nurses—working in well-lit, pleasantly attired corporate offices, from board rooms to processors—to develop and enact systems that forget they are manipulating the lives of real people.

This is the kind of system that succeeded in the reduction of D. to a chain of disregard, obstacles, and delays, all with the goal of ensuring that he would not get the treatment he warranted by contract and medical necessity.

Let’s get to the point: the main reason he would not get a referral to the only doctor and facility with the procedure he needed depended on the lack of a contract for lower reimbursement rates. That meant high costs—i.e. financial losses on some accounting file. There is no incentive to care about D. as a person, to uphold the sweet promises in his member booklet about their individualized, caring approach to “ensure quality “and to provide “right treatment at the right place at the right time” (a favorite rationale to justify insurance intrusion and control).

Not for D. What he got was no necessary treatment, at no appropriate place, and not at the time he needed it. He died instead—subjected to a kind of torture as he worsened each day, no doubt hanging on with hope, trusting that people really cared about him, waiting for the precious gift of approval—the coveted golden ticket for American medical care. His risk of death, at the hands of individuals who viewed him as an economic liability to avoid in every way possible, never appeared in his glossy propaganda.

This occurred despite the dogged pursuit by a treating physician who did not succumb to the “hassle factor,” an adroit tactic used to deter physicians from fights for what they know their patients need—actions that have become too expensive and time-consuming for doctors, no matter how much they want to help their patients get their necessary medical care. For the patients and physicians, it is a deliberately distorted game, one in which one player has massive resources to develop the rules and control the actions—most of which will be hidden—to use against the opposing players who are handicapped by debilitation, confusion, and powerlessness. What gamers would ever play in such a match?

Yet, we have allowed corporate healthcare to perfect these systems. It is legally sanctioned sacrifice of human lives to greed and profiteering. It only makes sense when we face the irrationality and the deadly menace of the model. Physicians and other healthcare providers spend years of grueling education and training to learn the complexities and skills for patient care. They carry personal, ethical, and legal responsibility. They suffer moral injury when they cannot fulfill their obligations and they bear the personal cost of direct suffering. Most of them are dedicated with tireless devotion to the intimate care of their patients. It is hard work. Yet a corporation can upend all of that with a few strokes on a computer.

Several weeks ago, my family doctor responded to a medical need on a Sunday. And he wasn’t one of the new “concierge” doctors for whom patients pay hefty fees to get what used to be standard medical care. He is a physician who works with some of the sickest patients, the kind that requires time and extra care, the kind that gets him in trouble with his employer and insurance companies. He shows up every day, and just recently added evening hours to accommodate the needs of job-bound people who cannot afford to take off from work or the high co-pays for urgent care clinics. He loves patients, but the practice is not only intellectually demanding, but physically and emotionally destructive, as he also has to juggle the administrative tasks and suffer the emotional toll of fighting for his patients.

When I apologized about making a request on a Sunday, he wrote: “I have been working on charting since 10 AM. I don’t have hobbies. I have medicine, and caring for other people is what drives me. I have the massive amount of administration tasks, but until retirement I shall slog through.” He is young and we should be frightened to think about how he will fare during the decades until he can retire. By all current evidence, he will burn out long before then. We are losing physicians, especially primary care, rapidly. The current statistics for increasing ways to escape—depression, substance abuse, destructive life choices, and even suicide, should shock us all.

This, then, is where we are. Medical care, at least until it is replaced completely by androids, AI, and cold algorithms, is still delivered mostly with human-to-human interaction. Good medicine requires attention, touching, listening, and caring. Patients are individualized, humanized. Eye to eye contact occurs. A doctor might have before him or her the 15th diabetic of the day, but no patient is just a failed pancreas that can be fixed with a computer formula to be dispensed in an allotted time of 10 minutes.

Let’s be clear about something else: insurance companies and other healthcare corporations engage in the practice of medicine. They wield power over exactly what and how physicians or other providers can and cannot do. They determine what patients can and cannot get. If D.’s treating physician had been cold and heartless, deciding that D. was too costly or didn’t deserve a particular referral, test, or treatment, then D. would have suffered harm or death. The causative thread would be clear, and the professional who made such an unethical, unprofessional decision could be subject to legal action and punishment in some way.

Yet, the corporation, with its company doctors and bevy of managers and executives, are far removed from the actual patient, who will be dehumanized by their distance and disregard. They will suffer little, if any, consequences, not likely even to their consciences. They are just doing their jobs. Jobs we have created and sanctioned.

However, the additional reality is that when a physician acts carelessly, negligently or callously toward a particular patient, it is one by one suffering. Unless a physician is incompetent, commits fraud or is sociopathic, few physicians engage in systemic actions that hurt large groups of patients. We have means to identify such offenders and can take action.

However, corporate healthcare systems are designed to process massive numbers of patients—more claims, more denials, more profit. It is the model for insurance success. We should not be surprised. When it becomes known that one patient is harmed or dies, they can quickly claim, if they acknowledge any responsibility at all, that it was a simple “mistake” or “mere anecdote,” (their favorite characterization), instead of a sentinel event signaling a calculated force for profits. It is no different from an industry that produces a known dangerous and defective product that is certain to cause harm and death. It is structural violence. We know what this is, as we have come to know from so many industries that cause us potential harm and death. And, as Lynch and Frank write: often “we can do little to avoid being the victims…because they can attack us even if we are vigilant...”[3]

Recognize this too: an injury to one is an injury to all.

But we have the “tip of the iceberg” problem. One is the messenger for the many. It is difficult, however, to measure the amount of suffering that results individually and collectively. We can roughly estimate “denial rates,” but companies are secretive and much of their operations and data is proprietary. Besides they never keep data on the suffering they have wrought. No one has. No one does. And an individual case has to be gripping and egregious, as well as rewarding enough, to get the interest of media or legal professionals to enable us to get tiny peepholes into lead-lined black boxes. It is a laborious and costly task for which many do not have interest, resources, or time.

To go further and unravel the innerworkings of systems, to follow the threads of origin, intent, agency, organization, functions, and responsibility, is too daunting for many who want untroubling involvement with real causes. Yet this is the very essence of structural violence. In depth analysis cannot be achieved with snappy social media postings in pursuit of quick clicks and facile “likes.” One can wriggle around the edges of a crisis, exploiting its momentary value, and never dare to go to its heart. We can spew out clever takes, seek media exposure, hawk our podcasts, and ride the wave of a current crisis—all while avoiding any real action. The powers that have made and support the systems—all of us in one way or another—indirectly and directly—provide so many of our livelihoods. Who of us dares to really put their personal and professional aspirations and success at risk for something greater than ourselves?

Yet this is the very essence of structural violence. It’s a legion that acts, not just a lone perpetrator. One rogue cell does not make a cancer.

This kind of corporate practice of medicine has consequences: the damage is spread to the whole of society—physically, morally, and economically, with the results extended beyond a single patient to families and communities, with a violation of trust and humanity. We are all potentially affected individually, never knowing exactly what we will face as vulnerable, imperfect, mortal beings. One thing for certain: something will happen eventually to us or someone we love. We know too that the increasing corporatization and profiteering of the health industry means that none of us, regardless of status, income, or privilege, is protected.

A broken healthcare system puts us all at risk. Any act of violence anywhere under any conditions eventually affects us all.

Although this has been more than a forty-year system in the making, we have acted recently as if the problem is new. It has taken the shocking murder of an insurance executive and the firestorm of response to bring forth a torrent of stories, some quite horrific. But these stories started four decades ago and have only multiplied in numbers and severity.

So much has been written over the past week–all of it cogent and compelling, all of it spot on. Some articles place the assassination in the context of systemic wealth and power disparities that may be pushing us beyond our individual and collective tolerances. Others preach simplistic blame and responses. Too many bemoan the complex entanglements that seem to render solutions impossible. Many articles direct their attention toward the specific individuals and organizations involved—this specific assassin, this specific executive, this specific health care organization. Whatever is said or written, remember that this singular act of violence is violence against us all.

But it is more. And it is deeply rooted.

Let us pause for a moment and consider some relevant issues. The outpouring of public experiences, not only with denials, but with struggle, defeat, financial ruin, and other sorts of devastation to lives—many heartbreaking and shocking for a country that claims the “best health care in the world”—should alert us to dangerous, fundamental problems, however difficult they may be to face and alter.

In a paper I wrote nearly a quarter century ago (2000), I observed:

“We ended a century of modern medical success with a great paradox. On one hand, the evolution of clinical science makes more medical conditions curable or relievable. On the other hand, the devolution of health care economics makes these successes less and less available—even to people who pay for them. Under the rubric of managed care, the practice of medicine radially shifts from physicians bound to patient best interest to individuals and organizations bound primarily to corporate best interest. We have the only health care system in the world in which care is limited or denied systemically by those who stand to financially benefit from its withholding. Patients, who once worried only about the ill effects of a devastating disease, now must also worry about the unprecedented harms arising from the management of these diseases.”[4]

We didn’t have to be here with this tragic event, with the deplorable assassination of a man with a wife and two children. So many of us had opportunities in the beginning and all along the way—policy makers, legal professionals, journalists, academics, and many other individuals—to understand the implications of what we set or allowed to set in motion. Our imagination and courage failed us.

Sure, when hundreds of tragedies began to occur in the 80’s and 90’s, the media exploded, academics wrote papers, politicians held hearings, activists pursued reforms. Pundits, executives, ethicists, and others (including me)—a stable of education and potential influence—had field days with all the fresh opportunities for publications, speaking, consulting and generally, as we know now, too much craven adulation or ineffective hand-wringing.

We tried to get substantive and effective patient protections and tinkered with regulations that looked and felt good, but didn’t translate well into real actions that made a difference. We took health plans to court and got big judgments and settlements, but in the end discovered the industry just considered it part of doing business. Lawyers on both sides thrived, until society and markets moved on to other hot topics.

Meanwhile, the health industry shapeshifted, polished its public relations and propaganda, and purged documents and communications that contained evidence of their schemes. And we let them get by with it, let them slip from the light, and they quietly grew in insidious sophistication. With our avoidance, apathy, complicity, and cowardice—or some combination—we have all failed and participated in the breaking of medicine.

Meanwhile, the business of health care morphed and metastasized like a raging cancer, and now ravages every nook and cranny of potential profit-making, causing untold suffering and death to patients in the process. Every aspect of medicine is monetized.

I thought we reached insanity 40 years ago when companies began to send new mothers and babies home after as little as 8 hours, but recently a company devised a novel cost-cutting trick: set a limit on the length of time that anesthesia would be covered. My sister-in-law, a surgical technician, gasped at the news, saying: “So let’s say you’re only covered for four hours on a CABG (cardiac bypass grafting) and then they turn off the gas. What are we going to do? Hand the patient a silver bullet to bite on. Why not have patients take an active role and prepare themselves for their procedure, start their IVs, ready their surgical rooms?” Fortunately, such a plan was so crazy, the company abandoned it. Outrage and action worked.

In 1999, a healthcare scholar wrote that:

“…managed care is marked by numerous ethics problems. Doctor-patient relationships have been damaged through the creation of new conflicts of interest for physicians, and through a marked reduction in the opportunities for physicians and patients to have trusting, non-commercial exchanges.”[5]

Now, a quarter-century later, look where we are.

As early as 1979, Dr. Edward Pellegrino, a revered bioethicist, argued that the ethics of physicians, and presumably all those from boardroom to bedside, who act in ways that constitute the practice of medicine, need to be grounded in awareness of the potential for the “damaged humanity” of patients.[6] What a quaint idea it turned out to be, when by 2001, we had a paper about the need to consider “criminal prosecution for HMO treatment denial.”[7] How much damaged humanity have we wrought to get us to 2024 when we have the death of an insurance executive, who becomes emblematic of the death of untold numbers over decades.

We can still do something about this. The tools already exist. If only we have the will to do so.

***

For nearly forty years, I have worked in every way possible to educate and change the systems that harm and exploit patients. I haven’t had an agent, a publicist, a brand, a platform, social media presence, or all those amplifying, force multiplying tactics to get “exposure.” I don’t know how to do self-promotion. By nature, my tendency to be introverted and reclusive does not equip me for a world in which one has to market a self and message. This is likely the source of my failure to make much difference.

I have erred on the side of belief in sincere, consistent commitment to difficult truths, ones that should move hearts, minds, and spirit to connect us with the suffering of others. And I have tried my best to live them. But it is hard for a small, soft, labored voice—a voice tuned by the quiet values of a mother, grandmother, doctor, nerdy bookworm, and a lover of all people—to get attention in chattering, clamoring echo chambers, especially when the messages aren’t edgy soundbites, clever punditry, or bumper sticker pabulum.

It saddens me then that I have known for years that it was inevitable that something explosive would happen. Interference in the care of patients and their families at a time of heightened physical, mental and financial stress is a recipe for disaster somewhere, somehow, sometime—to someone. Any one of us.

***

Back in the late 1980s a managed care company refused needed treatment. Mrs. G., who was not a youngster, showed up at the offices of the company armed only with an umbrella. There is no record of exactly how the conversation unfolded, but we do know that it ended up with a very surprised executive being hit on the head with an umbrella. In the 1990s, while I worked near an insurance call center, an angry father, whose child was denied critical, life-saving treatment, loaded up his car in Florida with guns and ammunition and headed for Kentucky. He was only intercepted in Georgia because his concerned wife alerted law enforcement.

Neither of these is an assassination in broad daylight. But we ignore the similarities at our peril. If you wanted to coarsely plot the progression of the particular pathologies of our current age, you could do worse than mark the line that runs from a heartbroken old woman swinging an umbrella to a younger, angrier, assassin wielding a ghost gun conjured out of the ether of the information age.

But we are a fickle species, flitting from one attention grabbing issue to another, rarely addressing the root problems. It is why we not only have corporate violence from our healthcare systems, but it “exists everywhere around us—it is a routine, daily occurrence.”[8] It occurs in faulty, dangerous consumer products; deadly effects of drugs and medical devices; contaminated foods; toxin chemicals and pollutants; environmental damages; firearms production…

The list can go on for pages.

Lynch and Frank have written that: “The study of corporate violence makes it clear that the average person is far more likely to suffer a violent victimization committed by a corporation than by another individual.”[9] A patient is more likely to suffer and die from the actions of a distant corporation than at the hands of an incompetent physician.

Recently, I lamented that:

“We live in a world of life-destroying complexities from which few of us have protection. Yet so much of this misery could be avoided or corrected. Webs of power and profit are spun from individuals who could choose different values and goals. The connections, though, between our actions and their effects can be negated by distance, disavowal, and disregard.”[10]

We have then lost our humanity.

Our legal system treats corporations as persons. However, they are also structures and systems designed and set in motion to achieve certain goals. Real people sit around and conjure up ideas, plans, missions, designs, organizations, policies and procedures, means for management and execution, and then revel in their genius. They set targets, offer perks, incentives, and bonuses to achieve their results. They propagate aims like “efficiency” and “quality,” yet we have one of the highest cost systems with the some of the worst outcomes in the industrialized world. And this is what we get from our self-proclaimed cost-cutting saviors.

It means the pursuit of money determines the values (or lack of) that organize our systems. And it is never enough. For some of us, it will never be enough. And that drives us to places of suffering—the kinds of suffering we all bear eventually in one way or another.

And while no human endeavor is ever perfect, when it comes to medicine there are just some things that are priceless and should not be for sale. When we are in the need of medical care, from minor to major needs, no one wants less attention, empathy, compassion, connection, and just plain value as a human being. We should never profit from the multiplication of human misery.

No one, from corporations to academics, ever did a study that confirmed that patients want people with less medical knowledge and responsibility to intrude between them and their providers. I am not aware of any research to demonstrate that patients have complained about the extra time a physician spent with them. There are no academic articles that include reports from patients’ requests for less listening and attention, more doctor time on computer screens, and quicker exits from exam rooms. Who defines “quality” and “efficiency,” and to whose purposes and gains?

Recently I witnessed a young woman, who appeared to work as a restaurant server, turned away from her necessary blood work to adjust her insulin—a life-saving medication for juvenile diabetes. She didn’t have $25 for her co-pay and asked if she could pay it later, after she got her check. All she got was a cold, flat “no.” “No payment, no service. See the sign.” Who thought that by hooking our medical care to begging, fear, humiliation, and pain that it would lead to “efficient, quality” health care?

In 1987, the discovery that I sentenced an unknown man to a death, while a piece of sculpture—eight times the cost of a life-saving heart transplant—was installed in a marbled corporate rotunda, sickened and saddened me enough to alter my life in medicine. I gave up my hard-earned dream to practice medicine directly for the pursuit of ethical, compassionate, life-giving health care systems. I expected the revelation that we were at a point in which a doctor could take a person’s life as an accepted part of a job would cause shock and outrage. It did not.

Now, here we are. Nearly four decades later and it still happens.

Do any patients in 2024 believe that any healthcare corporations today have their best interests at heart, that health plans would go to extended lengths to meet medical needs and prevent harm and suffering to real people? That they care one damned bit about the real person? Can anyone trust a healthcare corporation to put patients before profits?

With the unnecessary death of a corporate executive, a fermenting cauldron upturned with its years of its simmering frustration, anger, alienation, despair, fear, pain and loss, spilling its toxic brew, finally washing over us all. For decades, patients, families and communities have seen the emperor with too fine clothes, an industry attired flamboyantly with increasing inhumanity. Too many corporations, as Lynch and Frank argue, come to “accept outcomes such as death and injury associated with corporate profit goals as normal and even expected occurrences associated with typical behavior of corporations…as (they) create a value system supporting corporate violence as an unavoidable outcome.”[11] We have too easily accepted that this is just the way healthcare is organized now, that it is just the cost of doing business, or, more aptly for the American healthcare system, it is the benefit of doing business.

Yet, we cannot lose sight though that a corporation is comprised of individuals who make these outcomes possible. And this is all of us. We do it. We allow it. We experience it. As Abraham Joshua Heschel has said: “some are guilty; all are responsible.”

We are all vulnerable. But we have the intelligence. We have imagination. We still can have humanity.

We must find ways, to have courage enough to do more. I abhor cowardice—in myself most of all. The very real experiences of human harm and death are only increasing and worsening. We have had time enough to understand and respond to the causes. We have ideas, projects, plans, and tools available even now, as well as the abilities and means to consider new answers and actions.

To focus now only on the problem of “claims and denials” is not enough. It is as if we are the ones the poet Wisława Szymborska describes as sitting at a “conference table whose shape/was quarreled over for months:/Should we arbitrate life and death/at a round table or a square one?”[12]

In his book, "Utopianism for a Dying Planet: Life After Consumerism,” Dr. Gregory Claeys reminds us of the power to imagine "what might be but does not yet exist...(creating) maps of possibility..."[13] He writes about how this would urge us to ask more of ourselves, to realize that we have moral intelligence, and that our moral capabilities have not yet met their limits. He reminds us that we can have a better self—and a better world—if we would only aspire to realize it.

Our most important lived truth should be: No one’s life, and well-being, should depend on or come at the expense of another’s suffering.

***

We could begin by effectively holding all healthcare corporations and institutions accountable for harm and death, for negligence, malpractice, endangerment, even criminality when warranted, just as we would a treating physician. It won’t solve the root problems, but corporations are moved by economics. Threats and results from real accountability and economic liability can be a deterrent, and could lead to some internal modifications until more comprehensive reforms can occur.

As early as 2000, I wrote:

“When corporations and company doctors strip away patient particulars, when they quantify the nuances of a disease, when they rationalize away patient needs as just matters of economics, they vitiate a 3000-year tradition of patient-focused medicine. For this they should be held accountable, not only for the harm done to particular individual but for the harm done to the profession and the practice of medicine as a whole.”[14]

***

In the end of D.’s lingering death, it was discovered that there was no evidence in any company entry, exchange, denial decisions, or communication to him or his doctors that acknowledged that D. was a human being who mattered, who experienced pain, fear, confusion, despair, sadness, grief, abandonment, or anger. While the company shuffled papers for weeks, lingering and applying their heartless rules of a game they alone had the power and means to play and control, D. suffered bodily, emotionally, mentally and spiritually from a corporation’s organized, calculated bureaucratic violence.

At least his treating physicians would have touched him, looked him in the eye, listened to him, maybe held his hand or given him a hug. They are likely to have met his family, to have discovered he had a loving dog who would long for his real human presence—his smell, touch, warmth, care, reality, meaning—the real singular human essence that can never be recovered or replaced.

We can’t bring back those who have paid the ultimate prices—from the loss of one executive to multitudes from systems devised—but we can choose now to honor their sacrifices with pursuit of more human, compassionate, ethical, life-giving medicine and healthcare. But that takes heart and courage. And a willingness to deeply examine ourselves. What do we value? What are we willing to do for others? What are we willing to sacrifice in the interest of a better world together?

Victims, perpetrators, bystanders. We are all a bit of each. Thomas Merton, a monk with great heart and love for our human condition, wrote a book about “guilty bystanders,”[15] reminding us that we are all implicated in systemic evil, all beneficiaries of unjust economic systems, (but) many of us live far from the epicenters of human suffering. So, we need to put ourselves in the center of any tragedy. We need to understand our complicity. We need to think, feel, respond, and live differently.

***

We all will die at some point, but senseless, heartless deaths deprive us of being and meaning—a kind of death no one deserves, and the kind of death none of us should condone—ever.

Szymborska reminds us that: “Whatever you say reverberates, whatever you don’t say speaks for itself.”

[1] Szymborska, Wisława. MAP: Collected and Last Poems.

[2] Lynch, Michael J. and Frank, Nancy K. (2014). Corporate Crime, Corporate Violence, 3Rd Edition.

[3] Lynch and Frank.

[4] Peeno, Linda. February 1, 2000. “Managed Care and the Corporate Practice of Medicine. TRIAL.

whoof Health care Distorts Ethics and Threatens Equity.”

[6] Pellegrino, ED. 1979. Humanism and the Physician.

[7] Humbach, John A. 2001. “Criminal Prosecution for HMO Treatment Denial.”

[8] Lynch and Frank.

[9] Lynch and Frank.

[10] Peeno, Linda. 2022. “Voice Lessons” The First Person with Michael Judge.

[11] Lynch and Frank.

[12] Szymborska, “Children of Our Age.”

[13] Gregory Claeys, “Utopianism for a Dying Planet: Life After Consumerism.”

[14] Peeno, Corporate Practice of Medicine

[15][15] Merton, Thomas. Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander.