New Book by Alice Driver Might Forever Change the Way Americans Think About the People Who Work in Animal Meat Processing Plants Across the United States

Life and Death of The American Worker exposes the systemness of unsafe conditions, violence and exploitation | October 10, 2024 by Kimberly J. Soenen

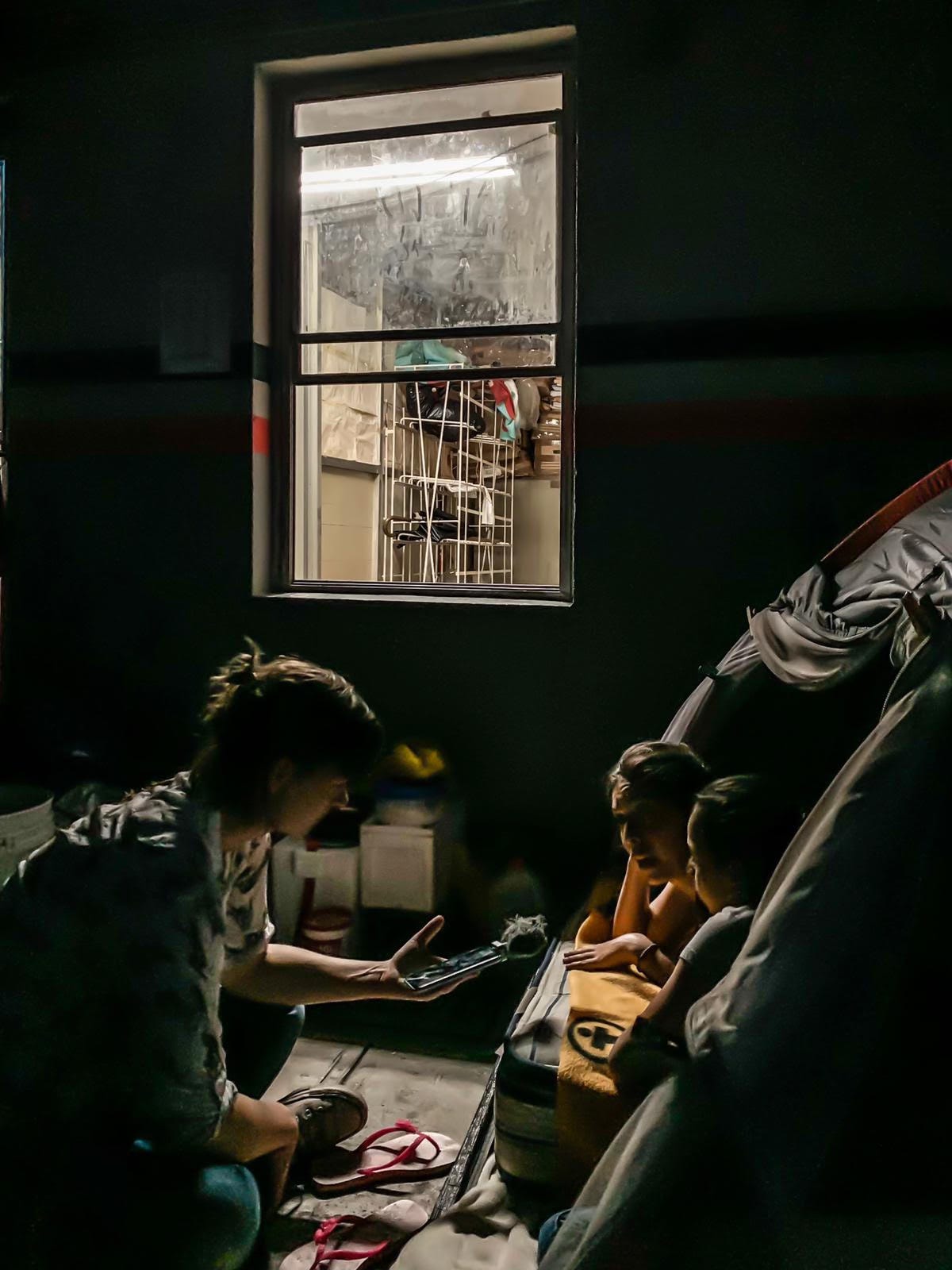

(Author/Journalist Alice Driver working in the field. Photo by John Stanmeyer.)

On June 27, 2011, a deadly chemical accident took place inside the Tyson Foods chicken processing plant in Springdale, Arkansas, where the company is headquartered. The company quickly covered it up although the spill left their employees injured, sick, and terrified.

Over the years, Arkansas-based reporter Alice Driver was able to gain the trust of the immigrant workers who survived the accident. They rewarded her persistence by giving her trusted access to their lives. Having spent hours in their kitchens and accompanying them to doctor’s appointments, Driver has memorialized many immigrants who survived the chemical accident in Springdale that day.

During the course of her reporting, the COVID-19 pandemic struck the community, and the workers were forced to continue production in unsafe conditions, watching their colleagues get sick and die one-by-one.

These “essential workers,” many of whom only speak Spanish and some of whom are illiterate—all of whom suffer the health consequences of Tyson’s negligence—somehow found the strength and courage to organize and fight back, culminating in a lawsuit against Tyson Foods, the largest meatpacking company in the United States of America.

The Life and Death of the American Worker is the culimination of the work.

Just days before traveling to Europe to present her findings, Alice was kind enough to answer some very specific questions about her work, her motivations for this focus and her thoughts related to worker health and Public Health.

Soenen: What was the most surprising aspect of this exploratory and investigative work for you and why did it jar you into focusing on this area of Public Health?

Driver: When I started this project, I didn’t know that Tyson Foods had on-site health clinics. Workers call the nurses at these clinics “Tyson nurses” and complain that they often don’t provide adequate or necessary care. When I interviewed a former nurse, who worked at several on-site Tyson clinics, she shared that nurses tried to do their jobs but felt pressured by Tyson staff —people without medical degrees or training—to send workers back to their lines to continue cutting chicken.

Soenen: What was the most difficult aspect of this work to confront either personally or professionally insofar as the role citizens play in the arc of nonhuman animal meat and slaughterhouses?

Driver: Tyson Foods made $53 billion in sales last year. Workers say that the company requires them to sign a legal document saying they will not speak to the media. One worker said a supervisor told her that if she spoke to a journalist, the company would send her to prison. Workers spoke to me at great risk, and that weighed on me during the four years I worked on this book.

Soenen: How has this work shape-shifted you personally or professionally in ways that you did not expect?

Driver: The complexity of this project required me to constantly problem solve. This project began as one article, and by the time I finished it, I had learned how to acquire an agent, write a book proposal, sell a book, work with a fact-checker, and coordinate a legal review of the book. Along the way, I faced a lot of rejection, but it did not shake my faith in the work.