In Search of Humanity with Her Camera Photographer Leah den Bok Captures the Personhood of the Unhoused

By Kimberly J. Soenen | September 15, 2023

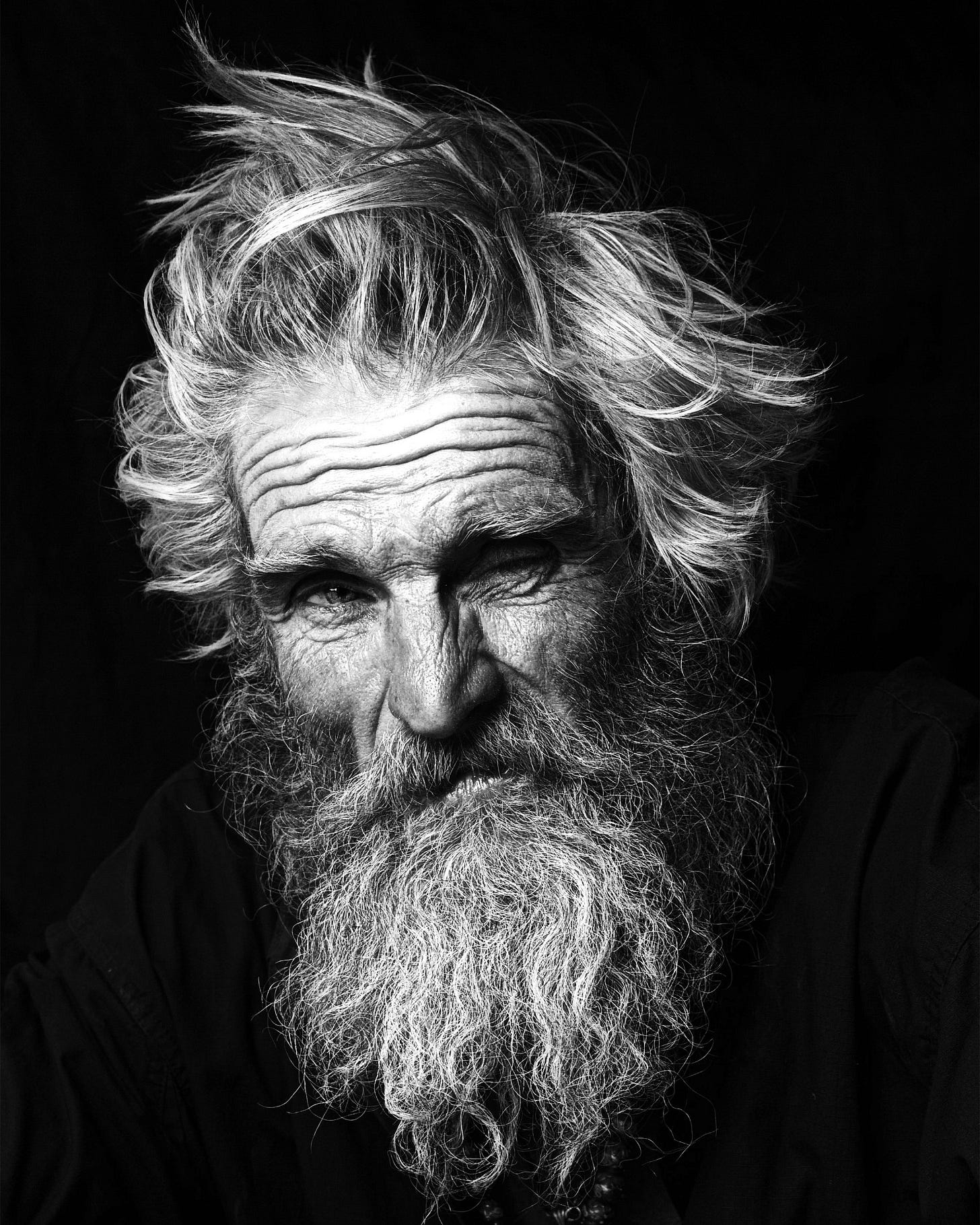

(“Duffy.” Photo by Leah den Bok)

For 20 years I lived on Upper Randolph Street in Chicago’s 42nd Ward. The 42nd drives more than 60 percent of Chicago’s economic engine power as it is situated in the heart of the city’s tourist district. Every major music festival and event—from Lolla, to Blues Fest, to NASCAR, to the Chicago Marathon, to private weddings and political protests — take place in The 42nd.

The 42nd is also where federal prosecutors, judges, and even the Governor of Illinois have resided. There are LEED certified skyscrapers, with underground parking spaces that sell in the thousands. Blue Cross Blue Shield, Health Care Service Corporation, and McKinsey & Company all have buildings on Upper Randolph Street. Chance the Rapper, Lady Gaga and the some of Chicago’s most elite professional athletes have lived in The 42nd.

Because so many “high profile” public figures live in this area, security is also high. Secret Service, State Troopers, Chicago Police, personal security detail and personal body guards are highly visible 24/7.

But The 42nd is also home to Lower Wacker, Lower Randolph and Lower Columbus—the underbelly of downtown Chicago that is anything but glamorous.

Just one flight of street stairs takes you into a small city of unhoused people, many of them addicted to opioids, barbiturates and narcotics. With people still reeling from the financial distress of Covid, inflation on the rise, and the child tax credit discontinued, people are struggling more than ever to afford housing and medical care.

Nowhere is the juxtaposition between “The Haves” and “The Have Nots” more visible in Chicago than Upper Randolph and Lower Randolph Streets. Driving Lake Shore Drive from the south, one can literally see the hierarchy tiers of wealth and poverty stacked like an indefensible erector set of disparity, caste and disregard.

When you live in a big American city, you learn to avoid eye contact with the unhoused. The sheer numbers of stuggling persons is overwhelming. Learned helplesssness sets in over time.

A few years ago, I took notice of the work of young photographer named Leah den Bok who has been producing a project called “Humanizing the Homeless.” Her portraits caught my attention for both their quality and compassion. I caught up with Leah recently to learn more about her project. We talked about respect for her subjects, what motivates her, and the best approach for capturing persons who are vulnerable.

“I don’t come across a lot of people experiencing homelessness who, like me, are in their 20s. From my experience, young men are often on the street because of family dysfunction, while in the case of young women it’s frequently because of abuse.”

-Leah den Bok

Kimberly Soenen (KS): Do you see many people your own age (23 years old) living on the street, and what is the most common reason they are unhoused at such a young age?

I don’t come across a lot of people experiencing homelessness who, like me, are in their 20s. From my experience, young men are often on the street because of family dysfunction, while in the case of young women it’s frequently because of abuse.

KS: Would you share one instance where you first felt empathy or a special connection to one of your subjects? Why did that one person’s story stand out or touch you?

I’ve always felt a special connection with a young woman named Lucy, whom I met a year or two into my “Humanizing the Homeless” project. I suppose I felt a special empathy for her because she was not much older than me. When I met her, she was in rough shape. She was sleeping with her boyfriend, Reilly, on a cardboard box beside the Eaton Centre—a mall located in downtown Toronto—and was addicted to opioids. I put my photo of her on the cover of the first volume in my series titled Nowhere to Call Home—Photographs and Stories of People Experiencing Homelessness. Her boyfriend told us that this action on my part helped to save their lives. In Reilly’s own words, it made them feel “human.”

KS: Do you know anyone in your own family who has been unhoused?

I was inspired to begin my homelessness project partly because of the story of my mother, Sara, who was once homeless herself. When she was three, she was found by a police officer wandering the streets of Kolkata, India, and taken to Mother Teresa’s orphanage. There, she was raised until, at age five, she was adopted by a family from Stayner, Ontario.

KS: In your experience, does mental illness cause homelessness, or does homelessness cause mental illness?

I think it’s both. Canada’s policy of deinstitutionalization in the mid-1970s resulted in many mentally ill individuals experiencing homelessness. I’ve met many people experiencing homelessness who were unable to care for themselves. They definitely needed professional help. On the other hand, we have met many people who have developed mental illness or worsened their mental state from the harsh reality of homelessness.

KS: How has your work impacted you, and what element of your work are you most proud of?

From the very beginning of my project, I’ve had two simple goals: first, to humanize people experiencing homelessness, and second, to shine a spotlight on their plight. Over the past eight years, I’ve received hundreds, if not thousands, of messages from people worldwide saying that my work has achieved these things for them. It’s very gratifying to receive these messages and to know that my work is making a difference in this way. This is what I’m most proud of.

KS: When you first approach people with photography equipment and large screens, do you find they are afraid or nervous? A few exceptional photojournalists started the “Camera Down Movement” years ago, meaning, sometimes you just have to talk and listen without shooting for days, and sometimes weeks, to established trust. How do you obtain a connection? And, what is your relationship with unhoused persons as a citizen first, and a photographer second?

I agree with the “Camera Down Movement” and do use it. When I find someone I would like to photograph myself, my dad, or whoever is with me as an assistant, will approach the person with my camera down. We will kneel to their level, make eye contact, introduce the two of us, explain what we are doing, and ask them if, for $10.00, I can photograph them and ask them a few questions. Usually, or about 80 percent of the time, they say yes. Only then, after I get permission, do I start taking photos.

KS: When you share photos with people, what is their response, and what has been the most moving response?

The most moving responses have come from family members and friends. For example, one time, I was contacted by several friends and family members of a woman I’d photographed in Toronto—including her daughter. It turns out that because of mental illness, she had left her family decades earlier and moved to the city. No one knew what had become of her. They pleaded with me to tell them her whereabouts. One of them said to me, “Please, please, please, please, please, let us know where she is.”

Sadly, she was hit and killed by a car before they could find her. Heartbreaking!

KS: Where is this long-term project work today, and what is your vision for it going forward?

Although I’m still trying to find a publisher for the fifth volume in my book series, I’m currently working on volume six.

I also have an exhibition and series of talks scheduled in October in Dallas, Texas. It’s a collaboration with Dr. Jonathan Palant, the founder and director of the Dallas Street Choir, and Professor Willie Baronet, the subject of the Prime Video documentary "Signs of Humanity.’”

KS: What else do you want to work on in the future?

I'm genuinely passionate about photography, and there are several exciting projects and areas I'd love to explore further in my career. Firstly, I want to delve deeper into portrait photography. Capturing the essence of an individual's personality and emotions through portraits is a constant source of inspiration for me. I aim to master various lighting techniques and experiment with different styles to create compelling and evocative images. Additionally, I'm keen on expanding my fashion photography portfolio. I am a fashion photographer and work on my project “Humanizing the Homeless” as a side project. But I work full-time doing fashion photography. Since I donate 100% of the profits I raise from my homelessness project, this is how I make a living. Furthermore, I'm interested in documentary photography. Telling stories visually and shedding light on important social or environmental issues is incredibly meaningful. I plan to work on more documentary projects that can positively impact and raise awareness.

KS: Up for a few more questions?

Yes!

KS: Nikon Canon, Leica, Sony…?

Canon.

KS: Black and white or color?

Black and white.

KS: Who are the three female / nonbinary photographers you most admire?

Natasha Gerschon, Sasha Samsonova and Vivian Maier.

KS: What one photograph by another photographer is indelible in your mind, and why?

The image Migrant Mother by Dorthea Lange. This image has always stood out to me because of the emotion evoked through the woman's face.

KS: Sushi pizza or poutine in Toronto?

Pizza.

KS: Favorite Toronto bands or vocalists?

Drake.

KS: Skateboard, train or bike?

Train.

KS: Country or place you’d like to visit?

Dubai.

KS: What would you say to the fourteen-year-old girl who has just picked up a camera for the first time?

Remember, photography is an art form, and there are no strict rules. It's a journey of self-expression and creativity. Enjoy every moment, and do not try to avoid making mistakes because mistakes often lead to some of the most valuable lessons. Keep that camera close, and let your passion for photography guide you on a fantastic adventure.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Learn more about Leah den Bok and “Humanizing the Homeless” here: