Look Up from Your Phones: Photographer Brenda Spielmann on the Paralympic Games, Parenting, Inspiration Porn and Luminaries

Part 2 | Special Series: Hold the Door Open—Making the Invisible Disability Community Visible by Kimberly J. Soenen September 8, 2024

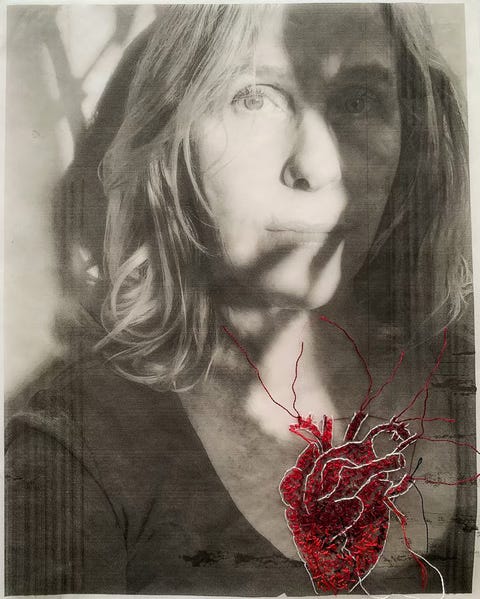

(Photographer Brenda Spielmann.)

In the fall of 2019, the “SOME PEOPLE” group exhibition opened in Chicago to record-breaking attendance. We extended the exhibition run because of the overwhelmingly positive demand and impactful response. The live exhibition was scheduled to tour and programs were booked through 2023, and then, Covid.

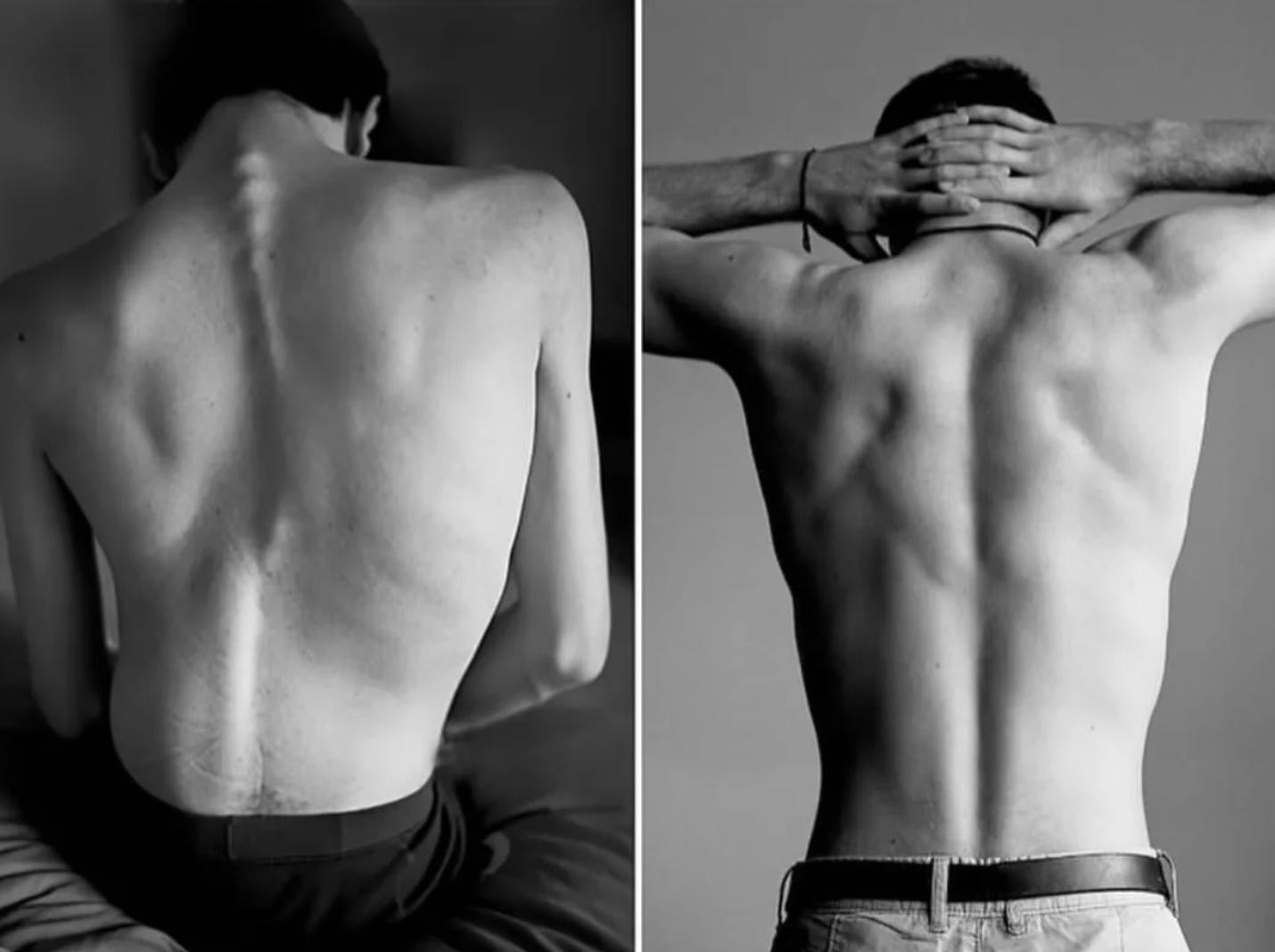

One of the relationships I forged during that curatorial process was with photographer Brenda Spielmann. For the exhibitoin, we printed a large scale photograph of her adult twin sons on silk. One son is disabled. The soft, flowing movement of the silks was juxtaposed against the backdrop of being a parent of a medically-complex child—that is, rigidity, forced acclimation and a world of barriers.

(“Twins.” Photo by Brenda Spielmann.)

Through her lens, Spielmann expresses the deep love she has for her family and at once communicates the isolation famliies with disabled children feel when colonized socially and ostracized professionally because life becomes unpredictable. Schedules are disrupted, priorities shift and emergencies sometimes supplant career demands. Unlike the unhealthy pace of modern-day society, the silks in the exhibition moved slowly, gently, telegraphing an aspirational metaphor for the need to slow down and make way for more grace, respect, and “other.”

Spielmann’s work has gained international attention including a recent feature in The Globe and Mail.

That opening night of the “SOME PEOPLE” group exhibition was well attended by contributors from all over the world. Healthcare industry professionals and the medical student community in Chicago came out in droves during the run. One of our disabled artists could not attend opening night because of flight accomodation issues. Another disabled artist had a “bad health day” and also had to miss the opening.

Spielmann and her disabled adult son traveled by car all the way from Toronto to attend. I learned how challenging it was to find a hotel in Chicago that was truly accessible. I was concerned they would experience difficulty safely navigating Chicago’s notoriously dangerous traffic. The bathrooms at the exhibition venue—built in 1911—were not truly accessible; the disabled parking spots were a long way from the building’s entrance; the wheelchair access ramp was in an inconvenient location; and the fire escape exits were all difficult to access. I was worried the freight elevator—which I made sure was large enough for wheelchairs and electric wheelchairs—would break down and trap someone the night of our event. I experienced the barriers, struggles, frustrations, concerns and inconveniences in the planning of the event that disabled people face hourly.

But, together, they made it.

Today is the Closing Ceremony of the 2024 Paris Paralympics at the Stade de France. Live coverage will start at 2:20 p.m. ET on CNBC and is also available to stream. As the games come to a close, Spielmann and I had a conversation about disability, her hopes for Health Philosophy Transformation and the difference between Accessiblity PR (Public Relations) and actual policy.

Soenen: First, what does photography achieve for you as a craft?

Spielmann: To me, photography is like that most trusted friend. Whatever I put into it, I get back. It keeps me sane and it keeps me happy. It's like air to me. That, along with any medium or art form that I choose to express myself with.

Soenen: The Paralympics close tonight in Paris. What emotions do the Games and the related media coverage this evoke in you?

Spielmann: Starting from the premise that we will all experience some form of disability at some point in our lives, the Paralympics are a great entry point for society to understand what it means to live with a disability. While the Paralympics have improved, more progress is definitely needed.

Paralympians have often been labeled as “superhuman” and “inspiring,” “brave,” and so on….which reflects such ableist attitudes that align with the concept of "inspiration porn," which was coined by activist Stella Young. This portrayal focuses on overcoming disabilities and being “cured" rather than recognizing Paralympians as elite athletes. The Paralympics, ideally, should have more coverage and run parallel to the Olympics, and it's important to note that the term "Paralympics" comes from "parallel," not "paraplegic.”

It is getting better, but I definitely see room for improvement…

(A “SOME PEOPLE” PSA Campaign: How Do You Define Health and Healthcare? 2019.)

Soenen: Let’s talk about divides, invisibility and all the ways in which some people are colonized by algorithms and policies: The wealth gap, the tech divide, the housing divide, the ability divide. You recently had an issue with your phone while traveling. What did this experience reinforce for you about how the modern world impacts us in the context of health, safety, and wellbeing?

Spielmann: I've always known that we are pretty much addicted to our phones and technology. If there's ever a blackout, people won't even know how to fry an egg without Googling it. The most dangerous part of all this is that we've stopped learning critical thinking. Schools are not incentivizing critical thinking, so kids don't learn to question. We've all become like sheep in the society we are following. Without realizing it, our phones have become an appendage that if/when we don't have our phone, we feel that we've been amputated, literally.

Soenen: What happened recently while traveling that amplified this feeling?

Spielmann: While I was traveling, my phone died. I was in a very remote area and I couldn't get in touch with the world. I'm not talking about social media. I'm talking about being able to access my emails, my banks, my everything. I was traveling with a friend who did have her phone, and I could her phone to get in touch with my family to make sure they were safe. Had I been alone, in terms of safety and well-being, I would have been at risk.

I couldn't even park a car because I needed an app to be able to park. There were no clocks in the hotel room, so I didn't know what time it was at any time. Not one clock. I didn't have my watch with me either. Interestingly, when I would ask the time in the streets, people would jump and think that maybe I was begging for something instead of just asking for the time. So, yeah, we are not in a healthy place. We are disconnected, not more connected.

Soenen: What wisdom can you share with parents of medically-complex or disabled children?

Spielmann: First of all, it depends if the child is born with a disability or it is an acquired disability due to an illness or accident, as the process of adaptation can be very different. Support from friends, family, and a community is crucial—it’s true that it takes a village to raise a child.

Parents should absolutely educate themselves about their child’s disability, as the medical system doesn’t always provide information and/or compassion. Doctors can sometimes be condescending, especially toward mothers. It’s super important for parents to be confident and advocate for their child. No one knows a child better than their mothers/parents. Of course, the medical know-how is crucial, but no one knows a child better than their mothers/parents.

Equally, self-care is really important. Parents need to take breaks and re-fuel. I personally know how difficult it has been asking for help and accepting it when others offer. As women/mothers (depending on the generation), we have this ingrained notion that we can and have to do it all (a bit of martyrdom can play into this) on our own, and that couldn’t be further from the truth. Ask for help. Accept help.

Soenen: One body of work you’ve produced is receiving international media attention, big brand commercial interest and solo exhibition buzz. Tell us about this work, and what it means to you as a mother, a caregiver, an artist and photographer?

Spielmann: “The Luminaries,” is a series of portraits I took of Para-athletes and Paralympians , and later I embroidered the works with a metallic thread. I had taken these portraits while my son was involved in wheelchair racing. He had gone to a training camp where all these other athletes were there. It was incredible to meet so many of them with such discipline and healthy bodies and the perseverance that it takes to be an athlete, let alone a para-athlete because there are always so many more barriers to overcome to reach that level of competition.

So, I decided to photograph them to show their strength and, literally, show their light. That is the origin of the name “Luminaries.” It also symbolizes someone who is an expert in what they do, including their ability to overcome barriers.

During the pandemic, since everything was so virtual, I was longing for the tactile and I decided to learn embroidery. I found out that I could do it on photographic paper, which took the work to another level. I continued the story from the initial capture and people have responded internationally.

Soenen: How does raising awareness about stigma, bias, and discrimination weave through your lifelong photographic work?

Spielmann: To me, because there is still stigma with people with disabilities, I thought that by creating these three-dimensional pieces, it invites the viewer to engage with it. They can get close, analyze, and the goal is always to bring visibility to disability, so that people become more comfortable with disabled bodies. Or, visibly disabled bodies. That's really the main goal.

Soenen: What do you want people to know about the Disability Community and families who have a disabled child or adult in their circle?

Spielmann: My work seeks to confront the stigma that still, to this day, surrounds disability in our society. I believe that disabled people are the most marginalized and isolated, living in hidden poverty and hidden social exclusion. Through my photography, I want to bring visibility to the disabled community, to those who are often perceived as the "other," and to challenge the concepts of “normalcy.”

I hope to create a space where the viewer can engage with this subject and my work can demystify what it means to be different. I want to encourage dialogue and a shift in perspective so that we see beyond the stereotypes. Then, ultimately, people will see the richness in humanity in all shapes, sizes, experiences, and what it means to be a human…just a human.

Soenen: You’ve lived in Canada and the United States and have experienced both approaches to, and models of, healthcare. The Canadian model is currently publicly-financed for the most part, and the United States model is dominated by the private commercial health insurance industry—a shareholder investment model. There is now a strong movement afoot in Canada to import private American model. What is your take?

Spielmann: The United States healthcare system was wonderful when we were there, and my son received excellent care from specialists, including numerous surgeries and so on. He was receiving Medicaid and it was truly, truly wonderful, state-of-the-art, in a very timely manner. When we moved to Canada, I felt it was very lacking. So, I cannot speak in terms of the U.S. healthcare system right now because I know things have changed, including that he has become an adult. And, the Canadian healthcare, as an adult, is pretty bad. He definitely falls through the cracks. There's not enough care in terms of getting services and support in a timely manner. Doesn't really happen unless it's a very big emergency. But I find it very lacking, and it's a bit scary because we don't get the care that he deserves.

Soenen: What laws would you like to see enacted in Canada to better society for disabled people?

Spielmann: There is one bill that was the act to reduce poverty. Out of around 24% of the population in Canada that is disabled, 50% of those persons live in poverty. This bill has a disability benefit, but it's still below the poverty line. Even though there has been an increase, it is impossible to live off it, especially in Toronto, which is such an expensive city, comparable I would say to the cost of living in New York City. What this means is a person living with a disability relying on this payment alone because they are unable to hold a job lives below the poverty level.

Soenen: And what about mobility and transportation improvements in design?

Spielmann: Yes. The other bill is transportation focused. The government has this plan to become “barrier-free” by 2050. They are also saying by 2025, they will build more accessible new subway stations and so on.

There is also the problem of snow removal. In the winter, when they push the snow to the sidewalks, it's impossible for a wheelchair to maneuver through that, including getting onto public transportation. When a bus opens the door, the wheelchair is left behind. Everybody climbs into the bus, and the wheelchair person is just there in the cold, unable to go onto the bus.

There is another form of transportation here which picks up the people from their home and takes them directly into where they need to go. It's the same as the public fare for a Metro. However, this service takes many hours. So, if you have a doctor's appointment at one o'clock for example, they might pick you up at 11:00am. You have to wait two hours at the doctor's and they might pick you up to bring you back home by three or four o'clock. So, you basically, for one appointment, waste a whole day. We do a lot of waiting.

Soenen: We will never be “post-Covid,” but what, if anything, has the world learned about the disability community in the aftermath of March 2020?

Spielmann: During COVID, people finally started realizing what it feels like to be isolated and to feel isolation. The concept of working remotely, which had been such a problem for people with disabilities (to be able to hold down a job and work from home) has changed. People can more readily work from home now. However, now that the world has semi gone “back to normal,” I think people forget what isolation feels like. We are accustomed to it. People with disabilities and their famlies are still struggling with that isolation daily, which is systemic.

Soenen: How do people bring in income with so many disruptions? How do they pay for a Personal Assistant (PA) or fit their homes to be accessible?

Spielmann: There are a lot of establishments and venues which are still not accessible for a wheelchair. The disability benefits simply don’t meet the cost of living needs at all. So, a lot of disabled people actually opt for medically-assisted End-of-Life (also known as Assisted Death) because they can't afford to live healthfully. They want to live with dignity and cannot. So that option is often a better one in the minds of some. It is incredibly sad and disturbing.

KS: Let’s pivot away from your identities as a mom, caregiver, advocate and professional photographer and get to know you more as an individual. Do you have a favorite band?

Spielmann: It varies over time, for now, the Hermanos Gutiérrez.

KS: Favorite meal or comfort food?

Spielmann: A very late breakfast.

KS: Most influential photographers living or dead?

Spielmann: Mary Ellen Mark.

KS: Who/What are you reading right now?

Spielmann: To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

KS: Salsa or Mambo?

Spielmann: Samba.

KS: Who is the Disability Rights leader you most respect and appreciate now?

Spielmann: Nina Tame.

KS: Bicycle, surf, swim or sail?

Spielmann: Swim and sail.

KS: Describe your greatest strengths in three words.

Spielmann: Humour. Curiosity. Neurodivergent brain.

KS: What is your hope for 2025?

Spielmann: More human connection. Real connection, not virtual. More overall lightness and actual fun in all aspects of life and society.

Soenen: If you could tell people one thing on the street when you are out with your son, what would it be?

Spielmann: I would like to tell people to put their phones down so they don't crash into his chair. Also, when people are staring at my son and me, especially little kids, they are free to ask questions. I welcome questions. We need to invite questions. Kids are inherently curious. Ask me anything about disability or life and I will answer.

Soenen: Thank you Brenda.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Commissions, Exhibitions, Assignments

The Globe and Mail feature (*Subscription required.)

Purchase Suboart Magazine Issue Number 28 here

Globe and Mail preview>